Dendrochronology: The Science of History

The Overfield Tavern Museum recently received the results of the dendrochronology investigations completed in December 2025 (see the full report here). The results are intriguing and help shed light on the history of Troy’s oldest building and original gathering place.

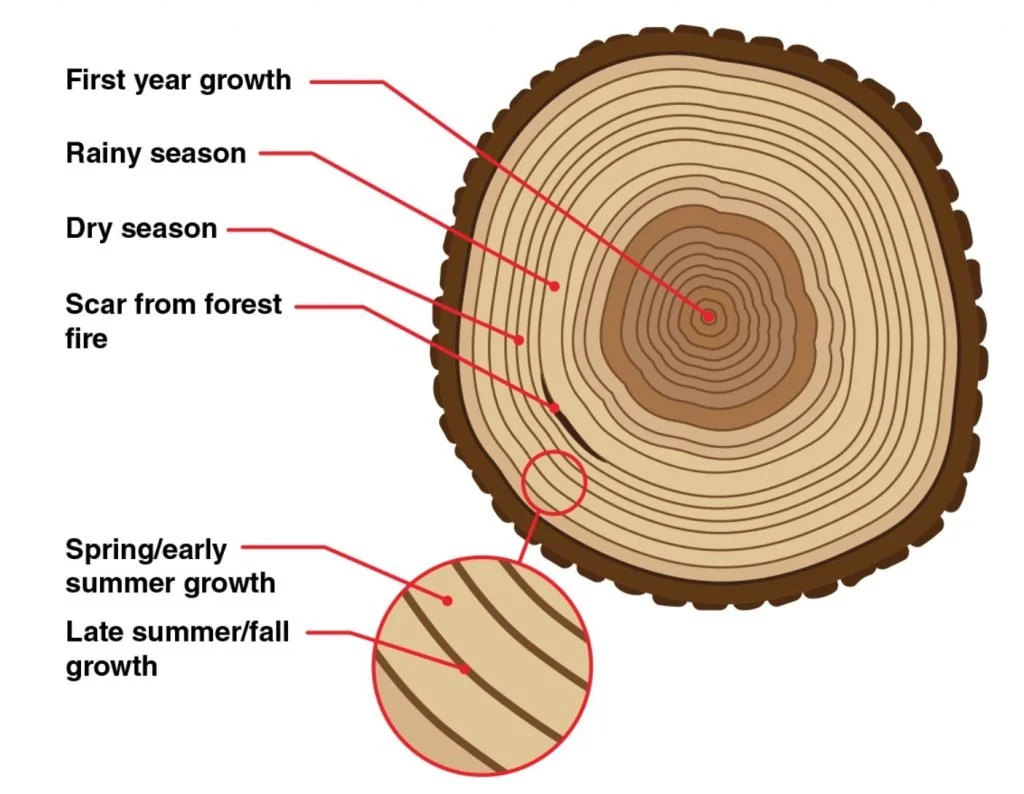

Dendrochronology, also known as tree-ring dating, is a scientific process whereby the growth rings of felled logs are examined to help date timbers in archaeological and architectural contexts. Dendrochronology can help date a building or other log construction to the exact year and season that the timbers were felled, providing what archaeologists refer to as a terminus post quem (TPQ), a Latin phrase meaning "limit after which," used to define the earliest possible date an artifact, timber, or layer could have existed.

With the Overfield Tavern, we hoped that dendrochronology would confirm that the two-story tavern fronting Water Street was built sometime before the fall of 1808, when Benjamin Overfield received a license to operate a tavern. But more intriguing to us was the date of construction of the one-and-a-half-story log structure attached to the rear of the tavern, which creates an ell encompassing what we commonly refer to as the dogtrot and kitchen. The date of construction of this structure was not previously known, but close examination after the fire suggested that it was not built at the same time as the adjoining log tavern. While it shares the same corner notching technique, its upper floor is not level with that of the tavern’s second story and the logs from each building abut but do not interconnect.

Interpretation of the smaller log structure has changed since it was rediscovered by the Hobarts in the mid-twentieth century. In 1948, it was believed to have once served as the county jail. [1] In the 1970s and 80s, that narrative changed and the structure began to be interpreted as the Overfield family’s first log house, built in 1803.[2] A few years later, interpretation had again changed, with the museum’s curator writing that:

The log cabin in the rear, now attached to the tavern by the hallway, was originally separate except for a roof connecting the two log buildings, so that one could pass from one to the other without getting in the rain. When we first obtained a copy of ‘Overfield History,’ we thought that the homestead cabin built by Benjamin Overfield in 1803 along the bank of the Miami River about 20 miles north of Dayton (referred to in Mary Rice’s account of our Benjamin), was the same as this log house back of the Tavern. However, after other evidence, particularly from John T. Tullis’ letter to Miami Union quoted previously in these notes, was found indicating that Overfield lived in Staunton until 1808, when he built the tavern, we must revise our theory about this little back cabin. But regardless of when it was built (1803 or 1808), it was undoubtedly the private living quarters of the Overfield family. Its fireplace and bake oven were no doubt used to do part of the cooking for tavern guests.[3]

The preliminary results of archaeological investigations completed in October 2025 revealed an ashy layer containing charcoal and artifacts under the southeast corner of the kitchen, east half of the dogtrot, and west edge of a later east addition. The archaeologists also uncovered in this ashy layer a feature consisting of burned earth flanked by two post holes in the southeast quadrant of the kitchen wing. Archaeologists interpreted the ashy layer and associated hearth feature as “a former activity area just outside the back of the original tavern building. This area was likely where various cooking, processing, and disposal activities occurred during the initial tavern use.”[4] They concluded that the kitchen and dogtrot were constructed after the original two-story log tavern.

We’ve been anxiously awaiting the results of the dendrochronology to help shed additional light on the kitchen wing, and we finally have answers. Analysis shows that the logs for the tavern were felled winter 1807/08 and spring 1808, supporting a construction date of summer/fall 1808. The samples taken of the kitchen wing are a little more unusual. They show that logs used in the structure were felled as early as summer 1807 and as late as winter 1814/15, providing a TPQ of 1815, seven years after the completion of the tavern.

Together, the historical record, archaeology, and dendrochronology tell us that Benjamin and Margaret Overfield built their tavern in 1808 and in 1815 constructed a kitchen wing on the back of the structure. In the intervening years, they used the backyard space to carryout daily chores and activities, including the use of at least one outdoor fire, perhaps used for activities such as rendering lard, doing laundry, or making maple syrup.

Why does this matter? As we continue to develop plans for the Overfield Tavern’s restoration, this information will help us decide how to interpret the site and its various spaces. We had considered interpreting the kitchen wing as the Overfield family’s 1803 log house, which would have made it the oldest building in Miami County. However, we now know that the building was constructed later and most likely used as a kitchen from the very beginning.

History is not written in stone and interpretations are always changing as new information and perspectives are uncovered. The dendrochronology of the Overfield Tavern has greatly enhanced our understanding of how the site was used by the Overfield family, which in turn will inform our interpretation of Troy’s oldest building and original gathering place.

[1] “Hobart Brothers Restore First House in Troy,” The Journal Herald, 2 April 1948, p. 5.

[2] Virginia G. Boese, “Construction Features of the Cabin,” Notes for Overfield Tavern Guides, 1989 Edition, p. 8; Donald A. Hutslar, The Architecture of Migration: Log Construction in the Ohio Country, 1750–1850 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1986), p. 122; Mary Harriet Overfield France-Rice, Overfield History two-volume manuscript in the private collection of the Overfield family, compiled 1859–1907, revised 1915–1917, transcribed by Virginia G. Boese in 1968, on file at the Overfield Tavern Museum, Troy, Ohio.

[3] Virginia G. Boese and Olive Ryan, “Construction Features of the Tavern,” Overfield Tavern Museum Guide Notes, p. 13, no date.

[4] Ohio Valley Archaeology, Inc., “Overfield Tavern Museum Recovery Archaeology, Troy, Ohio, Preliminary Results Summary,” December 15, 2025, unpublished report on file at the Overfield Tavern Museum, p. 7.